For years educators have known that today’s “typical” college student is not at all typical.

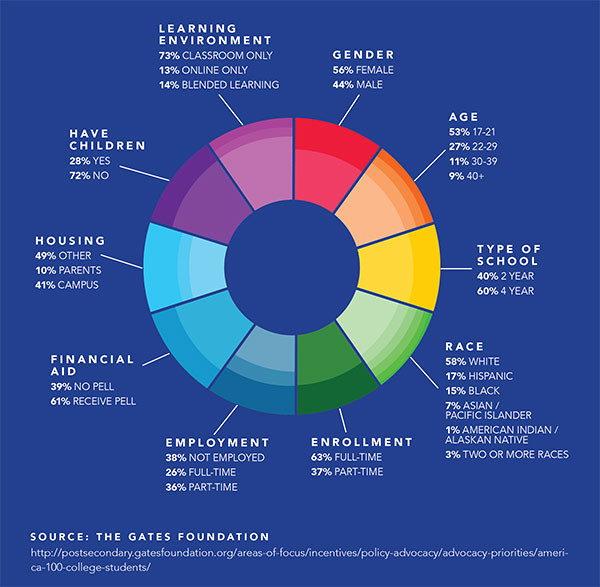

Long gone are the days of young, likely white, males exclusively reading the classics under spreading oak trees on the campuses of private, four-year institutions just after graduating from high school. We live in an age where 47 percent of college students are over the age of 21, 56 percent are female, and 42 percent are of a non-white ethnicity. A world where a majority — 62 percent — of today’s students work, either part-time or full, and 49 percent live off campus. Where 27 percent of students take some or all of their classes online.

It’s obvious that higher education has come a long way from the exclusivity of ivy-covered walls, but many would say there’s still a long way to go — especially considering the projected demographics of college applicants are predicted to change from today’s world in unique ways in coming years.

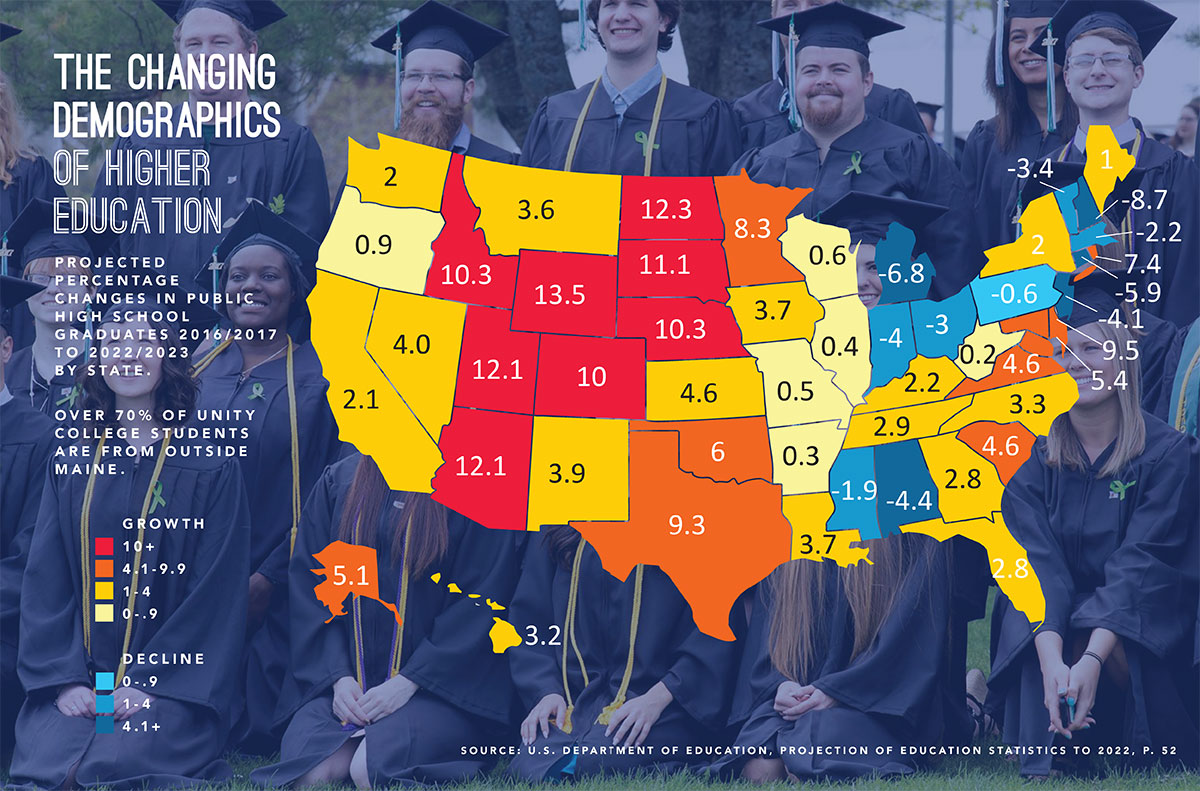

Projections from the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) indicate that after steady increases in the overall number of high school graduates over the last 15 years, the U.S. is headed into a period of stagnation. The pending national plateau is largely fueled by a decline in the white student population and counterbalanced by growth in the number of high school graduates of color — or, technically speaking, non-white public school graduates.

By 2030, the WICHE predicts the number of white public school graduates to decrease by 14 percent compared to 2013, with non-white public high school graduates projected to replace them to a varying extent until for every 100 white high school graduates “lost” in 2024 through 2028, there will be an increase of 150 non-white high school graduates.

In spite of this plateau, enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions is projected to increase by 15 percent between fall 2014 and fall 2025, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Enrollment rates are expected to increase far more for students of color than white students between 2013 and 2024 with 7 percent growth for students who are white, 28 percent for students who are black, 25 percent for students who are hispanic, 10 percent for students who are asian/pacific islander, and 13 percent for students who are of two or more races.

While total enrollment across the U.S. may have been slowly declining over the past four years, NCES projects enrollment rates to pick back up, with 2018 enrollment on track to surpass the nation’s peak 21 million students in 2010, and 2025 projected to blow that total out of the water at over 23 million enrolled students.

To top it off, the NCES predicts there will be more students over the age of 25 enrolled in degree-granting postsecondary institutions by 2025 than students under the age of 21. How’s that for overcoming the typical?

There is no doubt the overall change in demographics will present challenges for higher educational institutions, especially if they do not make moves to adapt. According to NCES, minority children are significantly more likely to be first-generation college students, who in turn are significantly more likely to drop out than those whose parents have college degrees. Plus, both minority students and older students are more than twice as likely to be low-income as “traditional” students, bringing even greater financial challenges to the equation, even as tuition costs across the nation continue to go up and up and up.

It’s more important than ever that Unity College continue to innovate and prepare for the future.

“If we as an institution can be ready and welcoming to all kinds of students we’ll be better off,” college President Dr. Melik Peter Khoury said. “We need to really look at how to become America’s Environmental College in every sense of the word, with a campus that reflects all the people of our nation. Sustainability science education is critical to the overall health of our world, and whoever wants to join our community should have every opportunity.”