Unity College alum Katie Haase conducts research on how climate change effects habitats, behaviors of animals

Growing up in New Jersey, in one of New York’s many suburbs, it can be a struggle for a young naturalist to find anything that resembles “wildlife.” So naturally, when it came time for Katie Haase, Ph.D. (‘07), who as a child was fascinated by the outdoors and wildlife, to choose her career path, her criteria were pretty simple. She wanted to work outside and with wildlife. How she would get there, however, was a different story.

“At the time I wasn’t actually sure what the degree would be called,” said Haase, recalling her search to find a college program that would be a perfect fit. “I knew I wanted something beyond biology, and I was struggling when I was looking at universities. ‘I know it’s not biology, I know it’s not zoology, I know it’s not environmental science.’”

Haase had a breakthrough at a college fair, when she was struck by a simple image of a student canoeing on the open water. It was something that Haase could relate to, herself having a passion for canoeing, so she decided to stop by the table and see what Unity College was all about.

Sure enough, listed under the majors she found something called “Wildlife,” and she knew she had found the right place. The 200-acre flagship campus gave her a respite from the New York suburb she was used to.

“I really enjoyed the courses, and I loved the relationship you were able to build with the faculty as an undergraduate student,” said Haase. “Being able to interact on a daily basis with Jim Nelson, Amy Arnett, and Emma Perry was just wonderful. I felt like they cared about what we were doing, and we also had opportunities to get hands-on experience that you wouldn’t get at many other colleges and universities.”

“One of the things that I think makes me most proud to be the President of America’s Environmental College, is seeing that from day one our students are immersed in experiential education,” said Unity College President Dr. Melik Peter Khoury. “Our faculty are engaged in research, and they involve our students in that. It offers students real-world applications for what they are learning, and prepares them for the next phase, whether that’s joining the workforce or entering graduate school.”

After graduating from Unity College, Haase immediately entered SUNY College of Environmental Science, earning her master’s degree in Conservation Biology while teaching Ecology and Evolution and working on research to characterize critical thermal environments for moose in the Adirondacks.

“In my first year of my master’s program, I was teaching seniors, and they were being introduced to things that I learned as a freshman at Unity College,” Haase noted. “It’s nice to see that what I learned at Unity College, a lot of people don’t learn until they do their internships.”

While at SUNY, Haase developed an interest in landscape, spacial, and thermal ecology, and although she had always had a passion for studying the effects of climate change on animal populations, she began to focus on the small-scale habitat relationship between animals and their thermal environment, and how that changes their behavior.

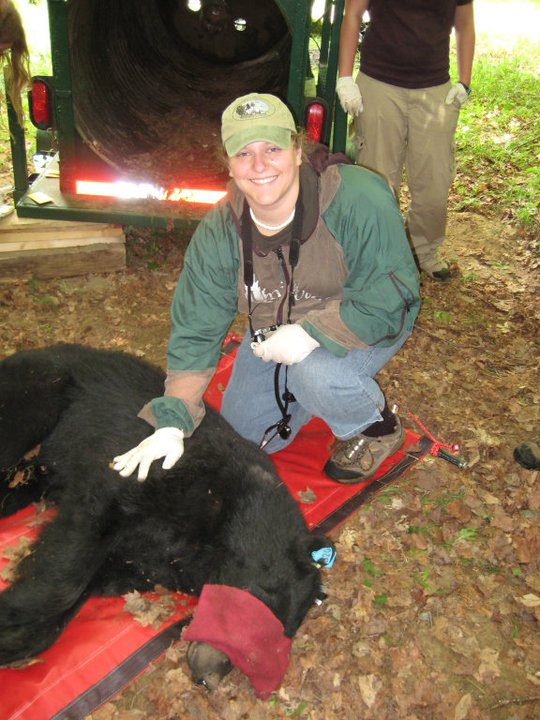

After SUNY, Haase continued her research at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, the US Geological Survey’s Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center as well as its Sirenia Project, where she looked into the habitats and behaviors of gypsy moths, wolves, and manatees.

Now, Haase is a postdoctoral research associate at Montana State University, where she has been venturing into caves throughout the West Coast to study bats, and predict the effects of white-nose syndrome, a fungus that changes the bat’s behavior causing it to starve to death. The work was featured in a New York Times article on February 18.

“It was spectacular!” said Haase on being featured in The Times. “One of the things I am currently trying to do with my science is to make it accessible to the public. As a wildlife ecologist, most of the research I do is for conservation purposes, and a big piece of conservation is outreach. So having our work featured in The New York Times felt like we were slowly making the public aware of a very important conservation issue — and shining a positive light on bats so the public can see how cute they are is always a plus!”

“It’s always great to see the work of our alum recognized in publications or on TV,” said Dr. Khoury. “But to be featured in The New York Times? Wow! Congratulations to Katie for not only doing this important work with bats, but also for helping to bring national attention to it.”

As Haase finishes her research at Montana State University, hoping to soon become a professor of Wildlife Ecology, she recently presented at the North American Society for Bat Research meeting in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, and taught a two-week biostatistics course at Hawassa University in Ethiopia. Though she leaves the option open to return to Ethiopia for a semester or two potentially as part of a Fulbright Scholarship, she has a clear vision of what she wants out of her future. “I do like to teach a lot. That’s what I’d like to do.”

However, her initial criteria of working outdoors and with wildlife still applies, of course.